Indian LNG demand has questions to answer

by Seth Haskell, Research Analyst, Global Energy Infrastructure

The large LNG SPA renewal between state-owned QatarEnergy and Petronet turned heads at India Energy Week in early February. The Indian importer agreed to buy 7.5mt/yr from Qatar until 2050, renewing earlier deals that had started in 2004 and 2008.

QatarEnergy followed up the deal a few weeks later by announcing it would build an additional 16mt/yr of capacity on top of the 50mt/yr North Field East and North Field South expansions already underway. Petronet’s CEO said in February that he expected LNG demand in India to rise to 150mt/yr by 2030, a sevenfold increase.

With approximately 200mt/yr of new LNG export capacity under construction globally and another 220mt/yr in serious development, many in the industry are hoping India can meet these expectations and become one of the global drivers of long-term LNG demand, holding prices high even as huge quantities of new supply come online.

The bull case for demand in the country looks superficially solid. India already imports c.30bcm/yr of LNG and is growing rapidly. GDP was up 7% last year, with similar growth predicted for this year. Gas makes up only 6% of the country’s primary energy mix, compared with 8% in China and 27% across the OECD. The government has pledged to increase gas’s share to 15% by 2030. At the same time, domestic gas production is not forecast to rise significantly in the near-term, and India has no international pipeline gas connections.

India also has the second-largest LNG regasification project pipeline in the world after China, with 32mt/yr of capacity under construction or in serious development. This year will see the completion of nearly 4,500 miles of gas transmission pipelines, particularly in northeastern India, bringing gas to previously underserved consumers. In the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), India’s primary energy demand almost doubles by 2040. If gas were to attain and then maintain a 15% share of primary energy demand, India could add another 190bcm/yr of demand by 2040.

But after more than a decade of growth, LNG imports in India fell in both 2021 and 2022 before growing again in 2023. India still does not have the buying muscle of China, Japan and South Korea—Asia’s LNG titans—and is forecast to remain less wealthy than they are now even after 15 years of rapid growth. High prices and difficulties with building infrastructure remain significant obstacles to attaining the sort of long-term LNG import level dreamed of by traders and producers.

Government subsidy

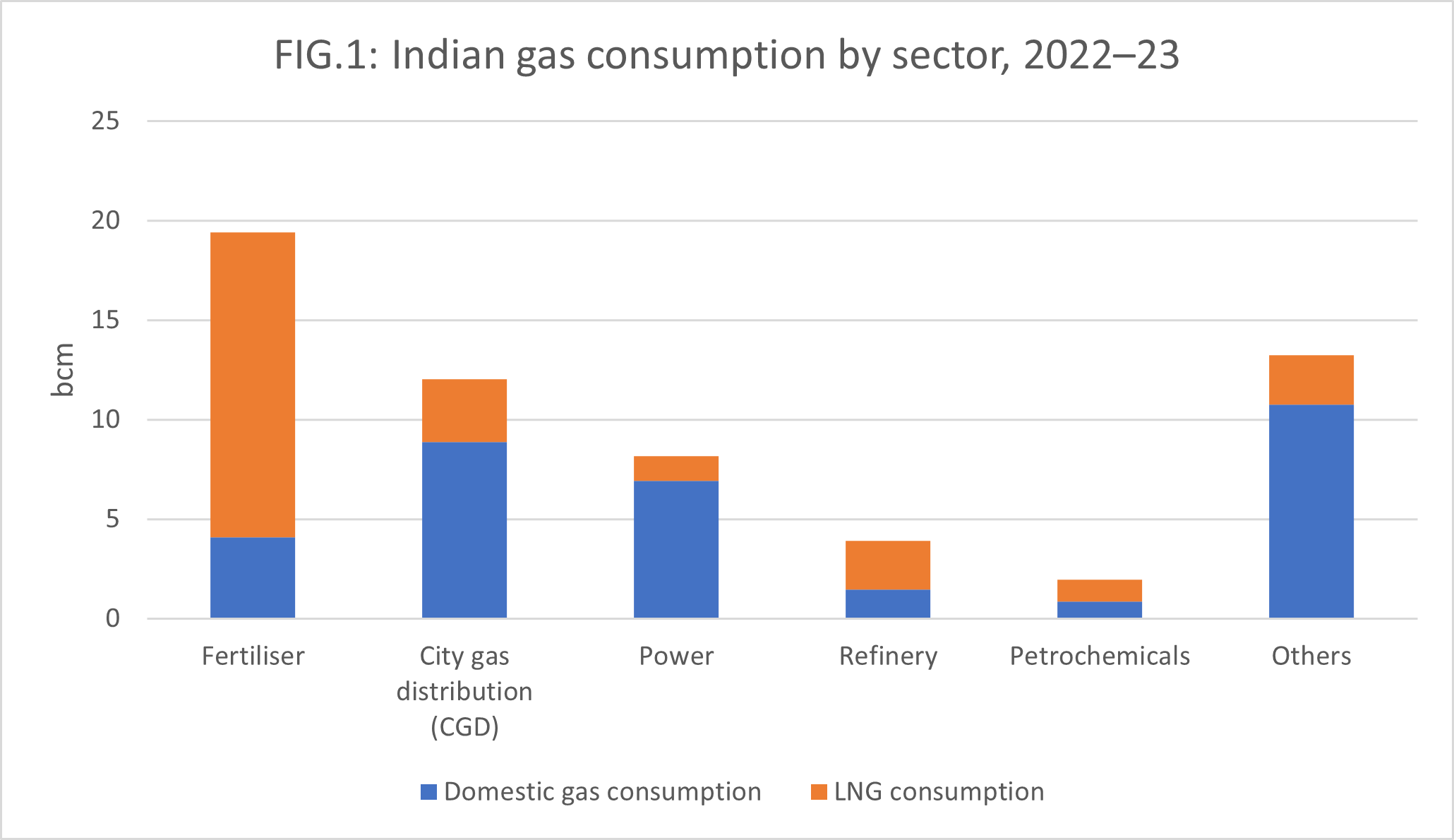

It is a bad sign that most of India’s LNG is consumed by the fertiliser industry. Over the 2022–23 fiscal year, fertiliser production accounted for 33% of India’s gas demand and more than 60% of its LNG demand. The fertiliser sector can afford to import this much LNG because it is the beneficiary of massive government subsidies. This includes tariff barriers, price controls on inputs and huge direct subsidies. This government support can cover a significant portion of the cost of production depending on the variety of fertiliser. Over the 2022–23 fiscal year, the Indian government spent more than $27b on this direct subsidy alone, with $21b budgeted for the 2023–24 fiscal year.

Other sectors make little use of LNG, with domestic gas dominating. Despite significant liberalisation last year, central planning still reigns supreme in the Indian gas market. Since April 2022, prices for domestic gas are determined by the volume-weighted average of the NBP, the Henry Hub, the Alberta gas price and Russian gas prices with a ceiling for most volumes of $7.92/m Btu. Prices can also be further adjusted for regions and sectors, and can depend on the gas producer. All prices remain well below the price of imported LNG.

LNG imports top up the limited supply of domestic gas in sectors that need it, trading at far closer to market prices that can easily be 50–100% higher than the price of domestic gas. Up to this point, when asked to purchase LNG at market price, Indian consumers and manufacturers have said no.

While the fertiliser sector could grow to further reduce imports, production would till top out at 160% of current levels—not enough to lead to an LNG demand boom on its own. India already consumes c.50% more fertiliser than China, while having only c.25% more arable land. And India’s available arable land is declining as the country continues to develop. India could also look to export fertiliser, as China has, but in the long-term India is simply not well-suited for fertiliser production because of the price of importing its primary input: LNG.

The government would also be on the hook for massive subsidies for the industry, something it is unlikely to be able to maintain forever. By comparison, China’s fertiliser production remained largely flat from 2006, before falling sharply after 2016 as the government cut subsidies just as the country’s most explosive period of LNG import growth got underway.

Power failure

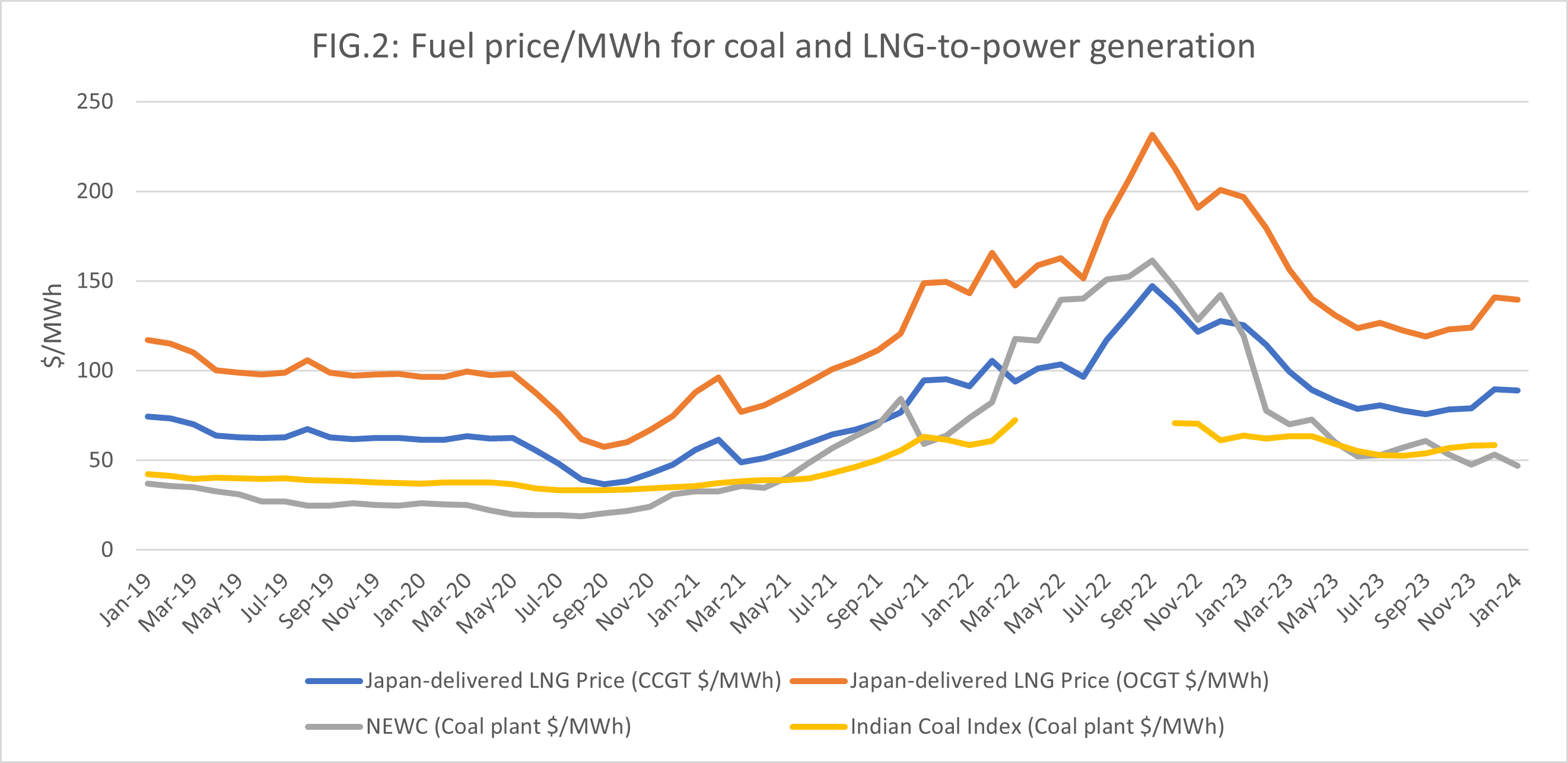

LNG will also struggle to compete in India’s power sector due to tough economics. Gas prices in the US hover around $2/m Btu, but LNG imported into Asia is far more expensive. In February, a contract for LNG delivery at 12.5% of Brent would have resulted in a price of around $10.50/m Btu. In the case of spot LNG, February prices were floating around $8–9/m Btu for both Asian and European cargoes. Meanwhile, prices for coal, LNG’s main competition in India, are sitting at around $5–6/m Btu.

Accounting for power plant efficiencies, coal generation fuel costs in February were around $54/MWh compared with $62/MWh for a combined-cycle gas turbine plant. And this is not an aberration. Since the start of 2019, the Newcastle Coal Index has averaged 46% of Japan-delivered LNG per 1m Btu. LNG-to-power has not been cost competitive with coal-fired generation over that period even when accounting for gas generation’s efficiency advantage. LNG will also face increasing competition from ever-cheaper renewables and other new energy technologies such as grid-scale batteries (see Fig.2).

Despite these difficulties, other emerging Asian countries have committed their national electricity policies to LNG-to-power. Bangladesh and Vietnam have pushed for more LNG imports due to climate concerns surrounding the use of coal and because they have gas-fired power plants supplied by falling domestic production. Rosy assumptions—shaken in 2022—about the long-term price of LNG also played a role. If these governments stay the course despite the economics, policy will drive LNG-to-power demand just as subsidies drive LNG demand for fertiliser in India.

But India has no such plans for building out gas-fired power. The country’s National Electricity Plan, adopted in 2023, envisions no additional gas-fired power plants through 2032, with additional demand being met by huge jumps in solar and wind capacity along with smaller increases in coal and nuclear. Gas will not replace coal in India as it did in the US and Europe.

Infrastructure difficulties

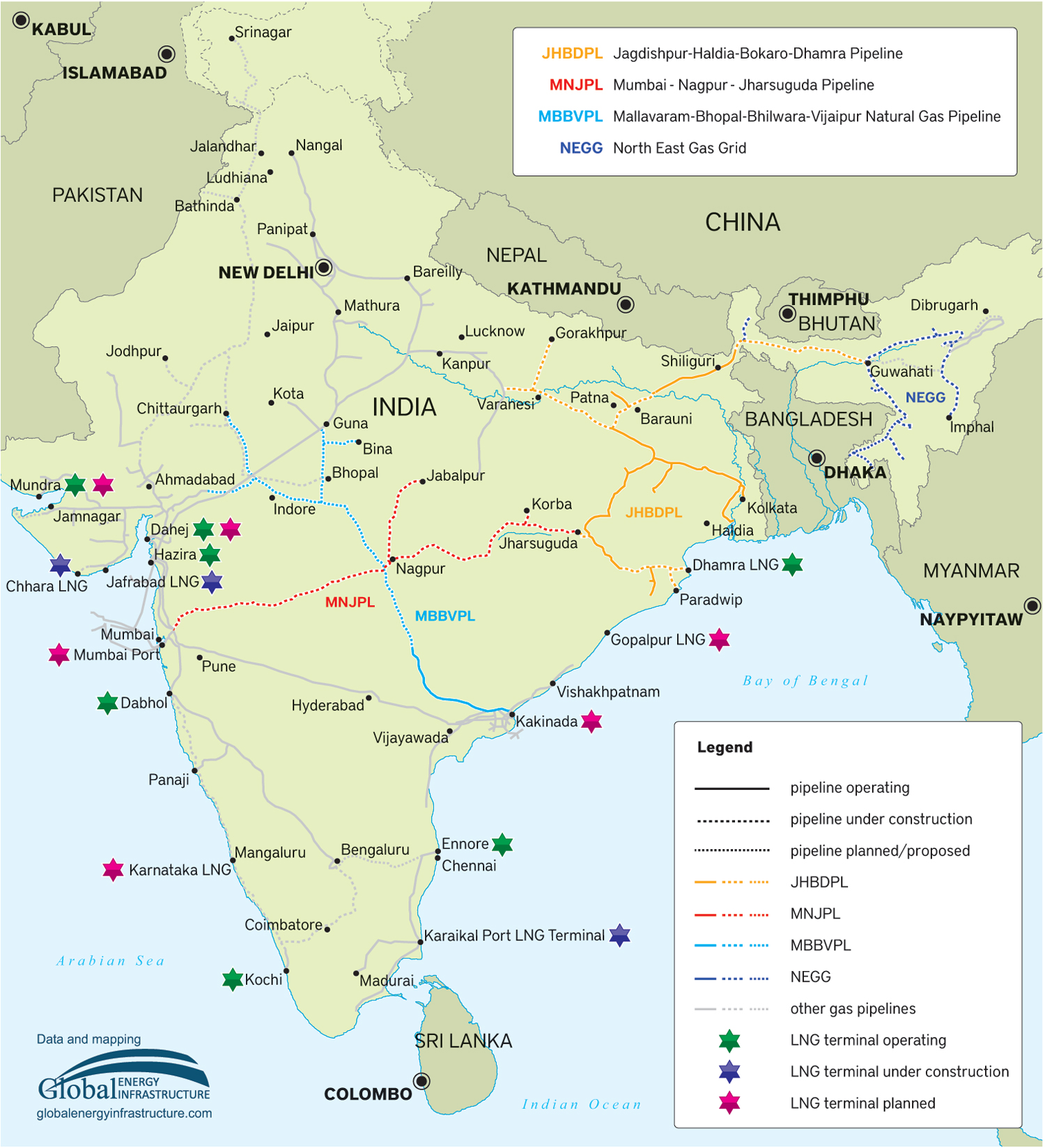

The regulatory process remains an obstacle to building gas infrastructure. In 2020, local gas distributor Gujarat State Petroleum Ltd (GSPL) was taken to court by regulator the Indian Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB) for failing to uphold the terms of its gas pipeline permit. The company had been permitted to build a 42in. pipeline running from the east coast to Vijaipur in central India, where there is still relatively little gas infrastructure. As of 2020, the company had constructed only an 18in. pipeline running about half the distance as ‘Phase 1’ of the project, with no start to ‘Phase 2’ in sight. GSPL argued to the PNGRB that “demand en route [the Mallavaram–Bhopal–Bhilwara–Vijaipur Gas Pipeline] looks bleak as there is no new gas-based power plant, fertiliser plant or any other gas-based anchor customer”.

The case remains ongoing as of publication, but the episode is emblematic of difficulties with developing gas infrastructure in India. The permitting process is difficult and limits companies’ options, while at the same time gas demand has failed to materialise at the scale needed to support large-scale infrastructure.

It is true that India has taken huge strides in gas infrastructure development over the last two years. The Northeast Gas Grid and Jagdishpur–Haldia–Bokaro–Dhamra pipeline systems have been partially commissioned, and Global Energy Infrastructure predicts they will both be fully commissioned by the end of the year. The Mumbai–Nagpur–Jharsuguda pipeline is also on track to open this year, one of the first major projects to bring gas to central India. The PNGRB envisions even more construction in the future, with more than 10,000 miles of pipelines planned for completion over the next decade.

But as GSPL’s case shows, infrastructure development is still troubled. All three major pipeline systems set to be completed will do so only after having been delayed several years, and the large Mehsana–Bhatinda pipeline being developed by GSPL in the northwest remains caught up in disputes with farmers who refuse to grant permission to build on their land without increased compensation—a common issue faced by Indian pipeline developers. The Mumbai–Nagpur–Jharsuguda connection has tried to work around this by building only on land already owned by the government (along a highway) but has still faced significant delays.

While India has a large slate of regasification projects, these terminals have also struggled to get off the ground. Hindustan Petroleum Company’s (HPCL’s) Chhara LNG terminal in Gujarat has been completed for more than a year but has yet to begin operations due to difficulties with building the connecting pipeline. In November 2023, HPCL was targeting early 2024 to begin commissioning at the terminal, but it has yet to happen. Local supplier AG&P broke ground on its FSRU-based Karaikal LNG terminal in 2020, aiming for a 2021 startup, but little progress has been made, with the company saying in 2022 it was considering moving the terminal. H-Energy has also struggled to setup several different LNG terminals, with its Jaigarh facility getting so far as to have an FSRU provided by Norway’s Hoegh arrive and promptly leave after less than a week, citing breach of contract.

Putting a number on it

Today, LNG has largely failed to find a place in India at market price and there are significant price-related obstacles to further growth. But India is fast-changing. Where will LNG demand in India go over the next 15 years? Fortunately, an excellent base-case for analysts to study exists. China is another massive Asian country that has recently experienced an extended period of rapid GDP growth accompanied by growing gas and LNG demand.

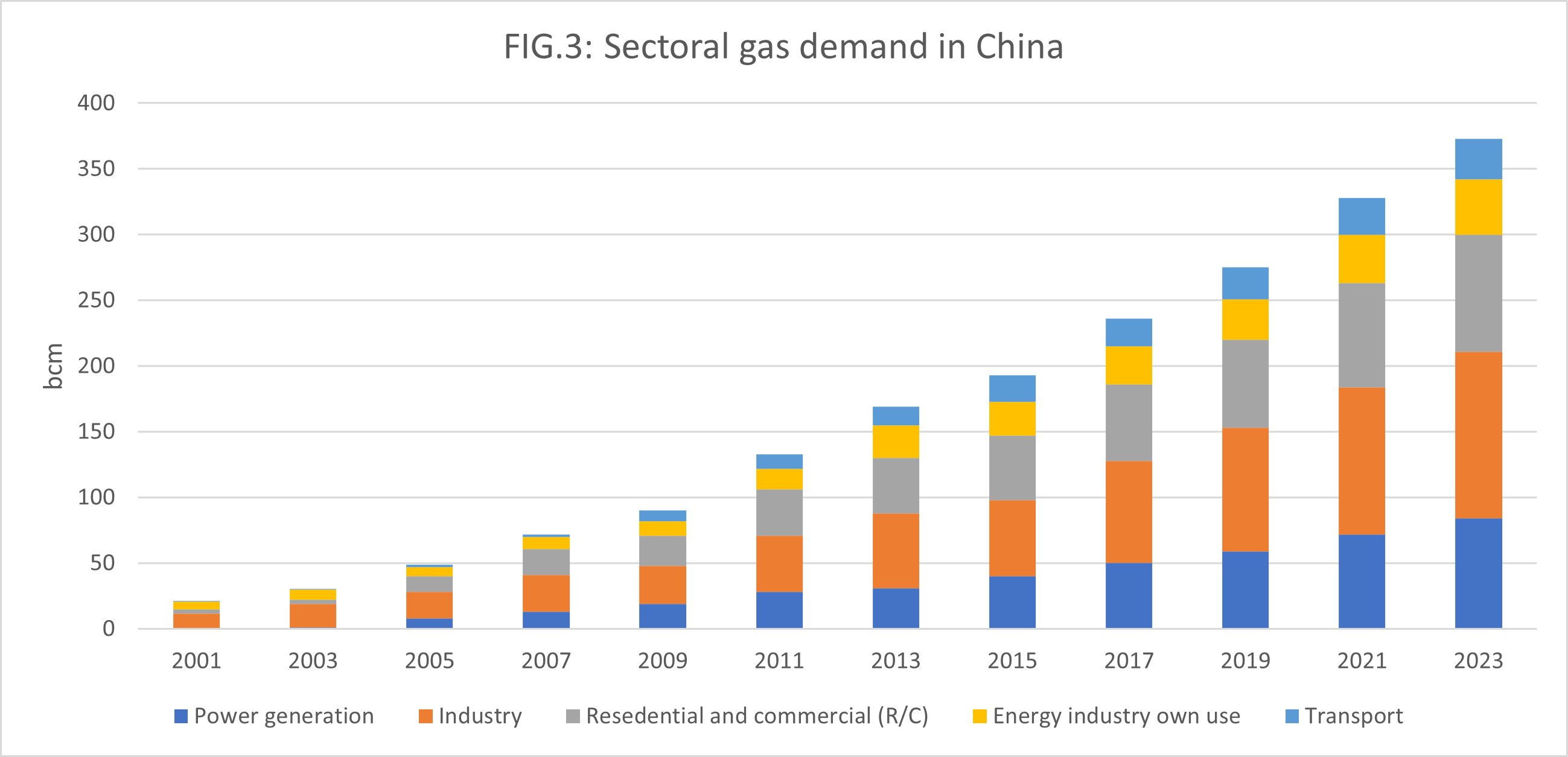

India’s GDP today is approximately equivalent to China’s in 2001 (GDP per capita is about 10% lower). And just like in India today, in 2001 60–70% of China’s industrial gas consumption was driven by fertiliser production supported by heavy government subsidies, although India’s current gas consumption of c.60bcm/yr is much higher than China’s in 2021—which was just 27.6bcm. Assuming a 5.5% average annual growth rate, Indian GDP in 2040 will be similar to China’s GDP in 2009. Over the period of 2001 to 2009, China’s annual gas consumption grew to 90.2bcm, an increase of 63bcm and a CAGR of 16%.

Importantly, this involved little in terms of expensive LNG. Imports started in 2006 and reached only 8bcm in 2009. LNG demand did not reach even 30bcm/yr in China until 2016, at which point GDP and GDP per capita had nearly doubled from 2009. China did not start buying truly enormous LNG volumes until after 2016, with imports peaking at 110bcm in 2021. This should be worrying for analysts counting on LNG demand in India to hold prices high. Even by 2040, India will simply not be as rich as China was during the period in which it fully embraced LNG (see Fig.3)

Furthermore, Chinese gas demand growth was driven by the industrial and residential and commercial sectors, which together made up 55% of growth from 2001 to 2009 and 58% of growth from 2009 to 2021. Power accounted for 27% and 23% respectively.

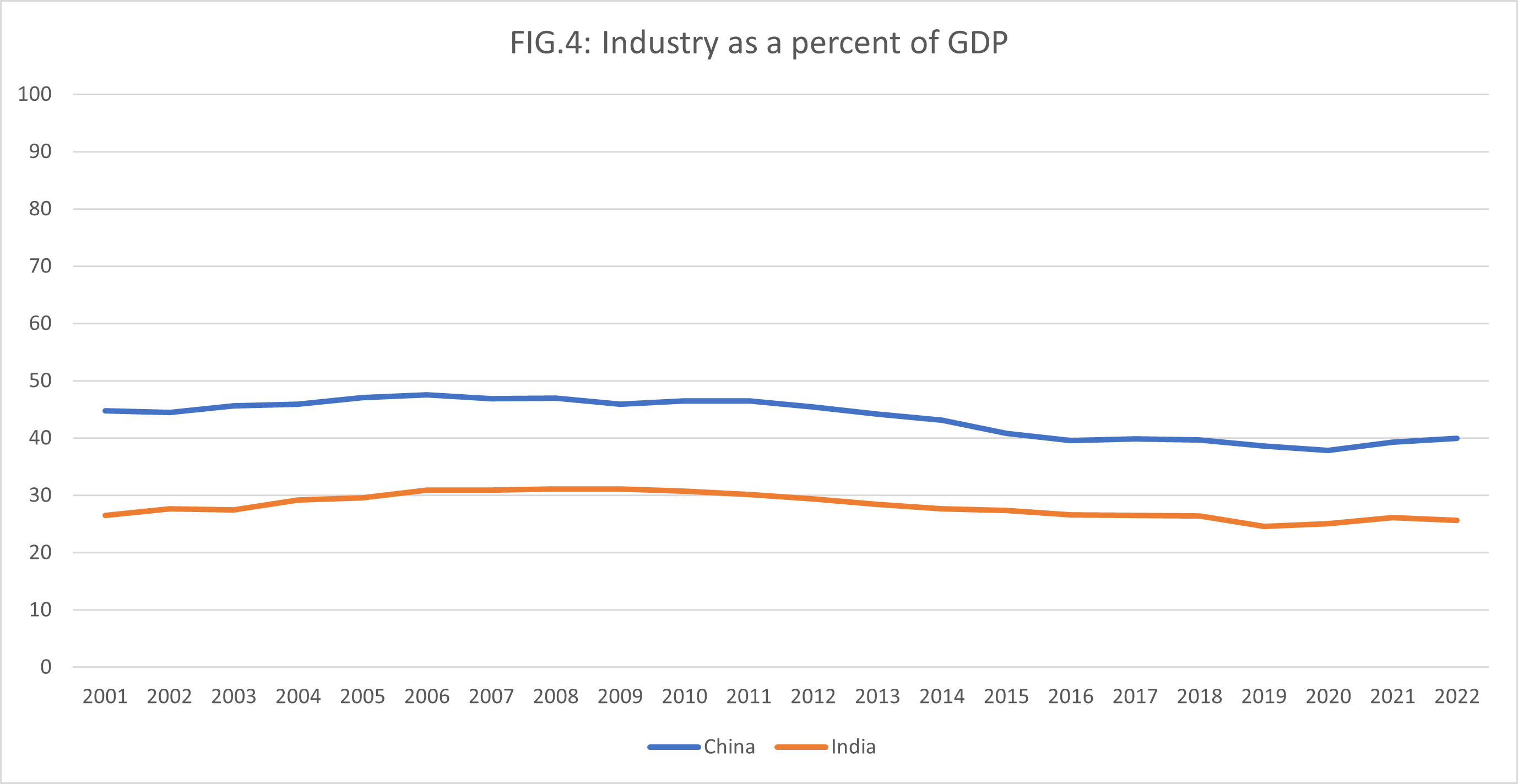

India is unlikely to match Chinese growth in either of these areas. Industry has accounted for 40–45% of Chinese GDP over the course of its growth miracle. In India, industry accounts for only 26% of GDP, with the share having fallen in recent years. Without a dramatic transformation in the structure of the Indian economy, growth in India will likely be accompanied by proportionately less gas-hungry industry (see Fig.4).

The residential and commercial sector is also unlikely to account for as much growth in India as in China for geographic reasons. In most markets with significant residential and commercial demand, the main driver is space heating. Relatively few people in India live in places where space heating is needed, and as a result this largest portion of residential/commercial demand is unlikely to materialise.

Adjusting for lower industrial demand, lower residential/commercial demand and a more competitive power sector, total Indian gas demand in 2040 can be forecast at roughly 97bcm/yr, an increase of 37bcm/yr over current levels. This number itself is optimistic, as demand in China was driven by domestic gas production and pipeline imports, rather than LNG. With higher prices for LNG, there is plenty of chance for India to undershoot the mark.

Downside risks

None of this is to look at two significant downside risks for LNG in India, the smaller of which is that the fuel will simply make no inroads in the power market. In the above analysis, rising demand in the power industry still adds up to a 10bcm/yr increase by 2040 as gas’ share of generation rises from less than 1% to c.3%. But competition in the power market is much tougher than during China’s period of rising gas demand. Renewables are proving to be a cheap and clean energy source that are a better option than gas for governments looking to cut emissions and improve air quality. Grid-scale batteries and other new energy technologies are also likely to muscle in on gas’ role in the electric grid. It is very possible that gas’ share of generation will increase not at all or fall between now and 2040.

The second significant downside risk for those looking to sell LNG to India is domestic gas. Production has been falling steadily since peaking at nearly 50bcm in 2010 and is now hovering around 30bcm/yr. But production is almost certainly held low by government price controls on domestic gas. While in the short term, it is likely that domestic production will continue to fall, it is far from unlikely that Indian domestic production will attain its previous height over the next 15 years, particularly if the government were to further liberalise gas markets. Growing domestic production would likely stimulate some gas consumption, but it will also eat away at LNG demand. Collectively, higher domestic production and less demand in the power sector could further lower eventual Indian LNG demand.

All about price

Price will be a factor. If LNG prices remain structurally lower than they were over 2015–21, when China’s LNG demand picked up and Japan-delivered LNG averaged $9.58/m Btu, perhaps Indian demand will jump higher than predicted here, but India will still not have the same purchasing power than China during its period of demand expansion and less willing to absorb high prices. And LNG prices in that range are hardly a dream scenario for traders and producers. Given that relative poverty, it is unlikely India can bid up prices far.

Comments